It wants to avoid upsetting markets, and is so far succeeding

At this point, almost everyone in global markets is familiar with the notion of higher-for-longer interest rates. Soon, they are likely to meet another concept as important for understanding central-bank policy: less-for-longer quantitative tightening (qt). This phrase describes how the Federal Reserve intends to continue reducing its assets to undo its huge bond purchases during the covid-19 pandemic. It hopes that a less-for-longer approach will ultimately leave it with a smaller balance-sheet than would otherwise be the case.

This may all seem quite technical. Indeed, in one metaphor much liked by Fed officials, tracking qt should be as interesting as watching paint dry. But the very dullness—if it remains that way—has crucial implications, because it would help to make balance-sheet expansion and contraction a staple in central banks’ tool kits for staving off financial crises. Although other monetary authorities are also in the midst of qt, the Fed plays a dominant role in this experiment as the central bank for the world’s biggest economy.

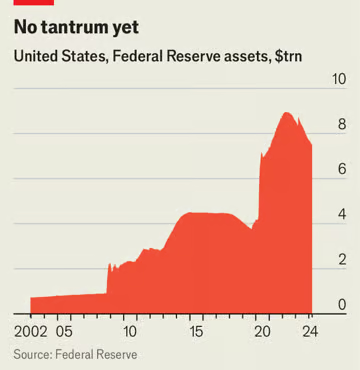

The Fed has already reduced its assets by about 16% to $7.5trn since the start of this round of qt in mid-2022—a slightly bigger reduction than its previous attempt at qt from 2017 to 2019 in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2007-09 (see chart). Yet its balance-sheet remains about 80% larger than in early 2020. Shrinking it further would give the Fed more scope to expand it again by purchasing bonds (often described as printing money) when the next financial maelstrom arrives. Managing to do so without crashing markets would also help answer critics who view quantitative easing (qe) as a cause of high inflation and bubbly asset prices.

The Fed has already reduced its assets by about 16% to $7.5trn since the start of this round of qt in mid-2022—a slightly bigger reduction than its previous attempt at qt from 2017 to 2019 in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2007-09 (see chart). Yet its balance-sheet remains about 80% larger than in early 2020. Shrinking it further would give the Fed more scope to expand it again by purchasing bonds (often described as printing money) when the next financial maelstrom arrives. Managing to do so without crashing markets would also help answer critics who view quantitative easing (qe) as a cause of high inflation and bubbly asset prices.

No one, including Fed officials, knows precisely the right size for the central bank’s holdings. The crucial measure is not the assets on its balance-sheet but its liabilities—specifically, the reserves held by commercial banks, which rise as a counterpart to the central bank’s bond purchases during qe. The Fed’s goal is to return banks to “ample” reserves, down from their “abundant” level today. Before the pandemic, such reserves came to about 10% of their assets. Now, they are about 15%. Given increased needs for liquidity, in part owing to stricter financial regulation, economists at Goldman Sachs, a bank, think a good level would be about 12%. This would imply that the Fed may want to shrink its balance-sheet by another $500bn.

Without any fixed target, the Fed is allowing itself to be guided by market signals. In particular, it is watching whether overnight financing rates for banks trade above the rate that it pays on their reserve balances. This would be an indication that liquidity conditions have become much tighter. Money-market ructions in the autumn of 2019, including surging short-term financing costs, led the Fed to bring its previous round of qt to a screeching halt. This time, it has avoided such instability.

Having got this far, officials now want to slow their asset reduction, betting that doing so will minimise the risk of market disruption and thus, over a longer period, maximise their balance-sheet shrinkage. With Jerome Powell, the Fed’s chairman, promising last month to start “fairly soon”, a fair conjecture is that the Fed will lay out plans for tapering qt after its next meeting on May 1st and begin to do so in June. Currently, the Fed is not selling securities but letting up to $95bn roll off its balance-sheet each month. A tapered qt may see it aim for a roll-off of roughly half as much.

The corollary of less-for-longer qt is that the Fed will probably continue to reduce its assets for the rest of this year, which means it may be shrinking its balance-sheet (ie, monetary tightening) at the same time as it cuts interest rates (ie, monetary loosening). Although that may sound contradictory, investors should in theory price in much of the impact of tapered qt as soon as the Fed announces it.

In any case, the big picture is just how few ripples the central bank’s balance-sheet reduction has caused so far—a contrast with both the turbulence of 2019 and the “taper tantrum” of 2013, when the Fed first discussed plans for trimming asset purchases. “People are getting more used to thinking about balance-sheet tools, and the Fed is more used to communicating them,” says William English, a former Fed economist. Watching paint dry is boring. But a well-painted wall can be lovely.