Scientists are finding that anti-obesity medicines can also help many other diseases

The gila monster is a poisonous North American lizard that measures around 50 centimetres and sports a distinctive coat of black and orange scales. This lethargic reptile, which mostly dwells underground and eats just three to four times a year, is the unlikely inspiration for one of pharma’s biggest blockbusters: a new generation of weight-loss drugs that has patients—and investors—in a frenzy. Originally made for diabetes, evidence is growing that they also have benefits in diseases of the heart, kidney, liver and beyond.

Since the late 1980s scientists believed that a gut hormone called glucagon-like peptide-1 (glp-1), which is secreted by the intestines after a meal, could help treat diabetes. glp-1 increases the production of insulin (a hormone that lowers blood-sugar levels) and reduces the production of glucagon (which increases blood-sugar levels). But glp-1 is broken down by enzymes in the body very quickly, so it sticks around for only a few minutes. If it were to be used as a drug, therefore, patients would have faced the unwelcome prospect of needing glp-1 injections every hour.

In 1990 John Eng, a researcher at the Veterans Affairs Medical Centre in The Bronx, discovered that exendin-4, a hormone found in the venom of the Gila monster, was similar to human glp-1. Crucially, the exendin-4 released after one of the monster’s rare meals is more resistant to enzymatic breakdown than glp-1, staying in its body for hours. It took more than a decade before exenatide, a synthetic version of the lizard hormone, created by Eli Lilly, an American pharma giant, and Amylin Pharmaceuticals, a biotech firm, was approved to treat diabetes in America. This breakthrough spurred other firms to develop more effective and longer-lasting glp-1 medications as a treatment option for diabetes, beyond injections of insulin.

Scientists had also been aware that glp-1 had another side-effect: it slowed the rate of “gastric emptying”, which allows food to stay in the stomach for longer and suppresses appetite. But the potential weight-loss benefits were not seriously pursued at first. It was only in 2021 that Novo Nordisk, a Danish firm, showed data from a clinical trial where overweight or obese patients were put on a weekly dose of its glp-1-based diabetic drug, semaglutide, which was then being marketed under the name Ozempic, for 68 weeks. The results were dramatic—participants had lost 15% of their body weight, on average.

Fat profits

The medicines that mimic the glp-1 hormone then became blockbusters. With close to half of the world’s population expected to be obese or overweight by 2030, according to the World Obesity Federation, demand for these drugs is surging—Bloomberg, a data provider, estimates that these medications will hit $80bn in yearly sales by then. The market is projected to grow by 26% per year in the next five years, compared with 16% per year for oncology drugs and 4% per year for immunology medicines, the two other biggest areas.

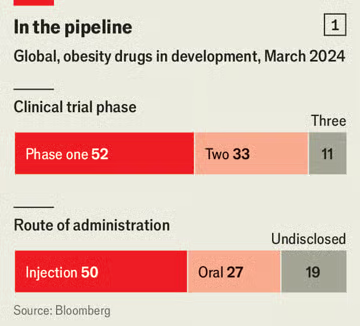

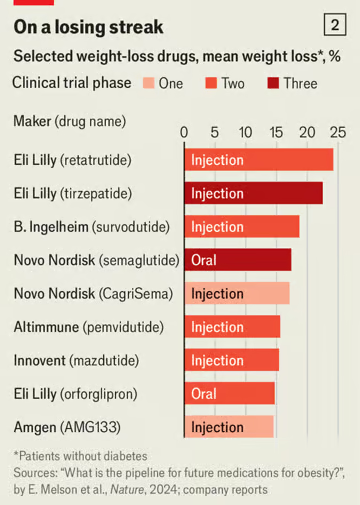

So far only three glp-1 drugs have been approved to treat obese or overweight individuals: liraglutide and semaglutide, developed by Novo; and tirzepatide, made by Lilly. But the market has already attracted a wave of competitors (see chart 1). Bloomberg tracks close to 100 wannabe drugs in the development pipeline. Most new therapies hope to outdo semaglutide and tirzepatide by crafting drugs that are easier to take, cause fewer side-effects or result in more effective weight loss (see chart 2).

So far only three glp-1 drugs have been approved to treat obese or overweight individuals: liraglutide and semaglutide, developed by Novo; and tirzepatide, made by Lilly. But the market has already attracted a wave of competitors (see chart 1). Bloomberg tracks close to 100 wannabe drugs in the development pipeline. Most new therapies hope to outdo semaglutide and tirzepatide by crafting drugs that are easier to take, cause fewer side-effects or result in more effective weight loss (see chart 2).

One issue is convenience. Both semaglutide and tirzepatide are injections that need to be taken weekly. Stop the dose and most of the weight returns within a year. Amgen, a large American biotech firm, is developing an anti-obesity drug that relies on doses once a month, and hopes the weight-loss effects will last even after treatment ends. amg133 activates receptors for glp-1 while blocking receptors of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (gip), a hormone secreted in the small intestine in response to food intake that stimulates the production of both insulin and glucagon. The company is now conducting clinical trials to find out if patients can, over time, be gradually weaned towards smaller doses.

Switching from injections to pills would also make the drugs a lot more tolerable for those who dislike needles. Novo is working on an oral version of semaglutide that works just as well as its jabs. But the pill requires 20 times the amount of the active ingredient as the injection, and must be taken daily. With semaglutide in short supply, Novo has had to push back the oral version’s launch. Lilly also has a daily pill that targets glp-1 receptors called orforglipron in late-stage clinical trials.

Switching from injections to pills would also make the drugs a lot more tolerable for those who dislike needles. Novo is working on an oral version of semaglutide that works just as well as its jabs. But the pill requires 20 times the amount of the active ingredient as the injection, and must be taken daily. With semaglutide in short supply, Novo has had to push back the oral version’s launch. Lilly also has a daily pill that targets glp-1 receptors called orforglipron in late-stage clinical trials.

Another drawback of glp-1-based medicines is the nausea and vomiting that frequently accompanies their use. Zealand Pharma, a Danish biotech firm, is developing a drug that is based on a different hormone called amylin, produced in the pancreas along with insulin in response to food intake. But unlike glp-1, which suppresses appetite, amylin induces satiety, or the feeling of fullness after a meal.

Adam Steensberg, boss of Zealand, says that in most people a hormone, leptin, is released from fat tissue that signals to the brain that the body is full. Obese individuals are insensitive to that hormone. Clinical studies have shown that analogues of amylin can make people sensitive to leptin again, helping them to stop eating earlier. Feeling full, rather than lowering appetite, may also reduce the feeling of nausea. Mr Steensberg says that results from early-stage trials suggest that its drug could achieve similar weight loss as glp-1 drugs, but with less nausea and vomiting.

Besides pesky injections and nausea, a bigger concern is that patients on these drugs do not just shed fat, they also lose lean muscle mass. Some patients drop almost 40% of their body weight in lean mass, a serious concern for older patients. To counter this, companies are trying out, alongside glp-1 drugs, medicines originally designed to treat muscle atrophy.

Regeneron, an American pharma company, is testing drugs that block myostatin and activin, proteins that inhibit muscle growth in the body. Taken with semaglutide, the combination could boost the quality of weight loss by preserving lean muscle. Similarly, BioAge, a California-based biotech, is testing a drug that can be taken alongside Lilly’s tirzepatide. The drug, called azelaprag, mimics apelin, a hormone secreted after exercise that acts on skeletal muscle, the heart and the central nervous system to regulate metabolism and promote muscle regeneration. In obese mice, the combination led to greater weight loss compared with tirzepatide alone, while preserving lean body tissue.

The slimming drugs aren’t just for shedding pounds. Because obesity is linked to over 200 health issues, including strokes, kidney problems and fatty liver, glp-1 drugs are proving useful in many other areas of medicine.

A recent clinical trial by Novo that ran for five years and enrolled more than 17,500 participants found that semaglutide cut the risk of serious heart issues like heart attacks, strokes, or death from heart disease by 20%. Novo believes that the heart benefits of the treatment are not due to weight loss alone, because the reduction in the risk of cardiovascular problems occurred early, before patients lost weight. In March semaglutide was approved by the us Food and Drug Administration for reducing the risk of heart disease in obese or overweight people, the first time a weight-loss medication has been approved for this purpose. Results from another clinical trial have shown that semaglutide reduced the risk of kidney-disease-related events by 24% in patients with type-2 diabetes.

Another weight-loss drug, survodutide, being developed by Boehringer Ingelheim, a German drug company, and Zealand, has shown promising results in being able to treat a serious liver condition called metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (mash). This is caused by the build-up of excess fat in the liver and can lead to liver cancer or liver failure.

In a recent trial of 295 patients, 83% of them saw a significant improvement in their condition when treated with survodutide, compared with 18% of those on a placebo. Survodutide targets receptors for glp-1 and glucagon. Waheed Jamal from Boehringer Ingelheim says that there is evidence that glucagon breaks down more fat in the liver compared with glp-1 and reduces fibrosis (build-up of excessive scar tissue in the liver).

Gut meets brain

Though a lot of focus has been on the action of these medicines on improving metabolic health, scientists are now uncovering that these drugs also engage with the brain and immune system, by interacting with glp-1 receptors in the brain. Daniel Drucker, a diabetes researcher at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto, found that in mice suffering from extensive inflammation throughout the body, glp-1 drugs reduced the condition, but only when the receptors in the brain were not blocked. When the brain receptors in mice were blocked or genetically deleted, the anti-inflammatory properties of the drugs were lost. This suggests that glp-1 drugs tame inflammation by acting on the brain cells.

For some this suggests that these drugs might be useful for treating brain disorders that are characterised by inflammation, such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Since 2021, Novo has been conducting a clinical trial involving more than 1,800 patients to test whether semaglutide helps patients with early stages of Alzheimer’s. This study is expected to be completed by 2026.

Dr Drucker sees the anti-inflammatory qualities of glp-1 medications as key to their versatility. He notes that, besides Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, chronic inflammation is a factor in many complications for people with type-2 diabetes and obesity, and affects organs like the kidneys, heart, blood vessels, and liver. If these drugs eventually help in treating these conditions, Dr Drucker believes that their inflammation-reducing properties could explain part of their success.

The appetite-suppressing effects of these drugs has also raised interest in their ability to curb cravings more generally. Researchers in Denmark investigated the effect of glp-1 drugs on 130 people with alcohol-use disorder. They found no overall difference in subsequent alcohol consumption between patients who used the drugs (alongside therapy) compared with those given a placebo. However, a subset of obese patients taking the drugs did end up drinking less alcohol. The researchers also looked at brain activity in the patients when they were shown pictures of alcoholic drinks—for those in the placebo groups the reward centres of their brains lit up; for patients on glp-1 drugs, activity in the areas of the brain associated with reward and addiction was attenuated, indicating a direct brain effect. Researchers are now exploring if the drugs might have an impact on how people use other addictive substances such as tobacco or marijuana.

All these findings are still early. Developing new drugs is costly and time-consuming. There are steep failure rates. Successes in the lab may not work in people, and results in small groups may not replicate in larger ones. But with the potential to treat many conditions well beyond obesity and diabetes, hope around the new drugs will only grow.