They face extinction at the next election

Like small nations (think of Bosnia or Kuwait), pipsqueak political parties can generate outsize effects. Consider Germany’s Free Democratic Party (fdp). The smallest of three partners in the coalition that has ruled the country since 2021, it holds just four cabinet posts, out of 17. The pro-business party is weaker still at the local level, serving in just two of the 16 state governments, and as a junior coalition member in both of them at that. Barely one in 20 Germans currently says they would vote for it in a national election. Yet this very fragility has made the fdp increasingly desperate to fire up its base.

That makes it dangerous. In domestic politics the party now constantly snipes at its coalition allies and flirts with the opposition, making an already unpopular government even more so. In Brussels, meanwhile, fdp grandstanding has helped gum up eu legislation on issues from vehicle emissions to supply-chain rules to the protection of nature. The actual damage that has been caused has, so far, been limited, except perhaps to the mental health of thwarted Eurocrats and to Germany’s reputation as a force for moderation. But as the spring budget-making season in Berlin heats up, and as European elections approach in June (followed by a trio of tight German state elections in September), the temptation for the fdp to undermine its coalition partners and sabotage European unity will only increase.

Founded in 1948, just before the German federal republic itself, the fdp has served in more national governments than any other party, albeit always in a supporting role. The party’s peak performance in a federal election, in 2009, saw it win 14.6% of the votes and a record 93 of the 600+ seats in the Bundestag (the number of mps varies slightly with each election). Yet at the very next election, in 2013, the fdp failed to reach the 5% threshold of votes cast that are needed for a party to win any seats in parliament.

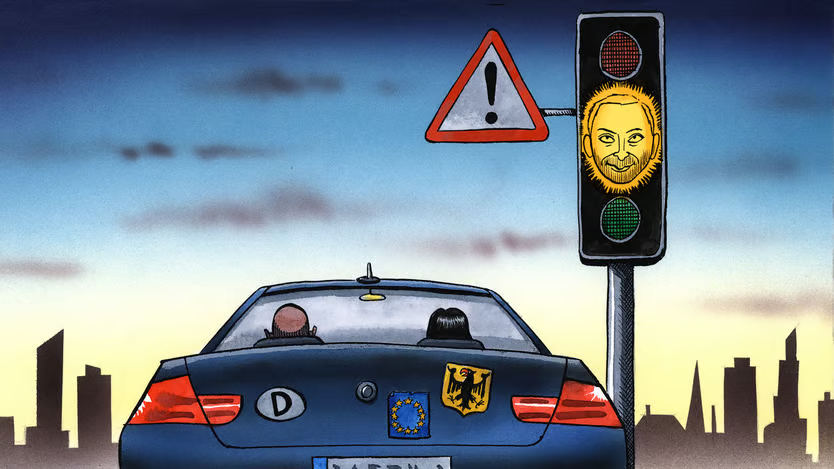

The party soon bounced back off the ropes. Under an energetic new leader, Christian Lindner, it found its way back into not just the Bundestag but national government. In the current coalition the fdp yellow flickers uncomfortably between the red of chancellor Olaf Scholz’s Social Democrats (spd) and the Greens’ obvious green; hence the “traffic light” nickname for the coalition. Mr Lindner serves as finance minister, a role he has not shied from using as a pulpit for the party’s agenda.

That has often meant taking a rigid stand over the “debt brake” that has since 2016 put strict limits on German governments’ ability to borrow. Appealing as it may be to many voters as a check against profligate spending, the curb has proved onerous in a time of multiple crises. Predictably, Mr Lindner has clashed with his cabinet colleagues, with those from the left-wing spd decrying threatened cuts to social services and the Greens complaining about delays to environmental measures, even as security hawks worry that he has failed to make fiscal room for what is sure to be a sustained rise in defence spending. Jens Südekum, a Düsseldorf-based economist, has described the finance minister’s rumoured plans for sweeping cuts in next year’s budget as “insane”, given Germany’s flatlining gdp growth.

Mr Lindner is neither an incompetent manager nor a political novice. He has faced internal pressure; in a vote in December just 52% of his party’s members voted to stay in the coalition. Yet Tarik Abou-Chadi, a teacher of European politics at Oxford, suggests that Mr Lindner’s focus on sustaining the fdp’s brand has put the party on a “destructive mission”. The feeble response from Mr Scholz has not helped. Mr Abou-Chadi suggests that in trying to keep peace in his coalition and protect the domestic agenda of its Social Democrat and Green components, the chancellor has given its smallest member extra leeway at the European level.

Hence, perhaps, the fdp’s stirring of trouble in Brussels. To be fair, plenty of other parties, typically from the right, agree on the same issues. What really annoys European legislators is that the fdp has repeatedly intervened at the finish line of the laborious lawmaking process. For a struggling party with barely 70,000 members to variously scupper, delay or force late-night work-arounds for legislation affecting 450m Europeans is infuriating. “If we don’t agree to what we’ve already negotiated, we undermine the entire European legislative process,” declared Eamon Ryan, Ireland’s environment minister, in late March, as a long-prepared law aimed at rehabilitating the eu’s rivers, seas and forests faced sudden flak that was partly initiated by the fdp and which has left it blocked.

Dangerous friends

Needless to say, the fdp’s supporters take pride in punching above their weight. They include powerful corporate interests. German carmakers were not displeased when the party last year succeeded in slipping last-minute exemptions into a proposed eu ban on selling new internal-combustion vehicles from 2035. And there was relief among smaller firms after a long-debated corporate sustainability due-diligence directive (obliging companies to ensure their supply chains are free of environmental or human-rights abuses) had its proposed ceiling for compliance raised from an annual turnover of €150m ($162m) to €450m.

These minor gains, which have hurt Germany diplomatically, have not improved the party’s ratings. In poll after recent poll, the fdp has skated along the edge of the 5% abyss; this week, it was at around 4%. Instead of rewarding the party for its fiscal probity and Euroscepticism, voters are turning to more reliably conservative, or even hard-right alternatives. “They have been so worried about their brand position that they have ended up hurting it,” says Mr Abou-Chadi. “In the end they would have benefited more from being part of a smooth-running government.”