What the Inflation Reduction Act means for the cost of health care

Buying prescription drugs in America can feel a bit like being a tourist haggling at a street market. First, a ludicrous “retail price” is mentioned (for your correspondent recently, $902 for eczema cream for a child). Then insurance is applied, followed by a layering-on of coupons (often printed by the pharmacist and then handed to themselves), discount cards and rebate claims. And yet even after all that, the amount of cash you pay out of pocket is still steep by international standards (the cream ended up costing $273).

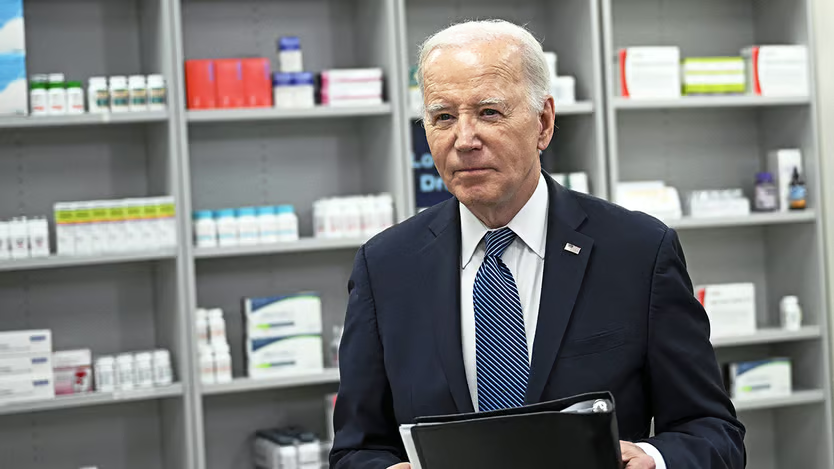

Americans agree on few things, but lowering the price they pay for medication is the most popular policy position in American politics, tied with support for Social Security. Nine in ten say this should be an important or top priority for Congress. In his state-of-the-union message Joe Biden spent a full three minutes on the topic. Yet only one in four say they are aware of his attempts through the Inflation Reduction Act (ira) of 2022 to reduce prices. This is something he needs to rectify.

At least as interesting as the direct impact of the law is the question of what the indirect ones might be. Americans spend twice as much on prescription medication per person as comparable countries, according to Peterson-kff, a health-research group. This spending is skewed by branded drugs with no competitors, so-called non-generic drugs. These make up 10% of prescription drugs but 80% of spending. Adjusted for inflation, spending on prescription drugs has increased from $101 per person in 1960 to $1,147 in 2021.

The ira, which was mainly a climate-change and industrial-policy law, did actually have some provisions designed to bring down prices (although not in the short term). One politically important one relates to Medicare, the public-health insurer for the elderly which covers prescription drugs for 50m people. The ira empowered Medicare administrators to negotiate with (or maybe dictate to) drugmakers, which they had long been forbidden to do.

A gentle, circling motion

This should eventually reduce the price consumers pay. In the near term, the ira also capped some out-of-pocket drug costs. The first to feel the effects of these measures are people with diabetes who need insulin, a drug for which Americans pay several times what Europeans pay. A national out-of-pocket cap of $35 per insulin prescription per month has meant that, since January 2023, millions enrolled in Medicare now pay less.

Another tangible result is an annual cap on out-of-pocket spending. Doug Hart, a 77-year-old from Arizona with heart disease, previously spent about $7,000 per year on prescription medication. Under the new cap, which is being phased in, he will be on the hook for only the first $3,300 this year, before Medicare foots the rest of the bill. From next year, the cap will be lowered to $2,000. “The way I see it, Biden is saving me $5,000 in out-of-pocket drug costs [and] I can go and see my grandkids in Chicago instead,” he says.

These measures have been relatively easy to implement because, if anything, the pharma industry welcomes them: they make drugs cheaper for consumers while the government picks up the difference. But Mr Biden’s law also gives Medicare a mandate to negotiate drug prices directly with manufacturers and penalises those that raise prices above inflation. This has met with more hostility from the industry, which argues that it will crimp innovation. Yet it is this part that will make a difference for taxpayers: without it, the price caps for consumers will just push high drug bills on to the government. Mr Biden’s claim that he has already saved American taxpayers $160bn thanks to these negotiations is misleading, because it relies on projections of future government savings.

Negotiations between the government and Big Pharma are under way behind closed doors. Drug companies are keen to reassure shareholders that the government’s proposals are not as outlandish as feared. Yet at the same time they have filed several lawsuits challenging the legislation. One way or another, the federal agency that administers Medicare will publish a list of the “maximum fair price” for each of the first ten negotiated drugs by this September, with the intention of introducing these discounts by 2026. Medicare spending on these ten drugs more than doubled between 2018 and 2022.

There is also the question of what the knock-on effects of the ira will be. Mr Biden has said he will try both to increase the number of drugs subject to negotiation and expand the $2,000 out-of-pocket cap to people with private insurance. Once the prices that Medicare pays for expensive drugs are published, this might increase the bargaining power of private insurers too. “Now that the government has these new tools, there are huge opportunities to go beyond [the ira],” says Richard Frank of the Brookings Institution, a think-tank. “If you can suddenly negotiate more drug prices, earlier in their life cycle, or these prices apply to the entire private market, then suddenly this is not an incremental change—this is a sea change,” says Benedic Ippolito at aei, another think-tank.

The president’s campaign team will be hoping that enough people notice the new, reduced Medicare drug prices in September—just in time for the election. But another scenario is just as likely: Mr Trump wins and claims credit for Mr Biden’s achievement, because the price reductions would not actually come into force until 2026. That would be the Trumpiest move. Either way, patients should benefit.