How to dismantle an industrial icon

“The difficulties inherent in such a reorganisation were many and serious.” In 1893 that was how Charles Coffin, the first chief executive of General Electric (ge), described merging three businesses into what became the legendary American conglomerate. More than 130 years later Coffin’s latest successor, Larry Culp, must have similar feelings about doing the reverse. On April 2nd ge split into two public companies: ge Aerospace, a maker of jet engines, and ge Vernova, a manufacturer of power-generation equipment. A third, ge HealthCare, a medical-devices firm, was spun off in January 2023.

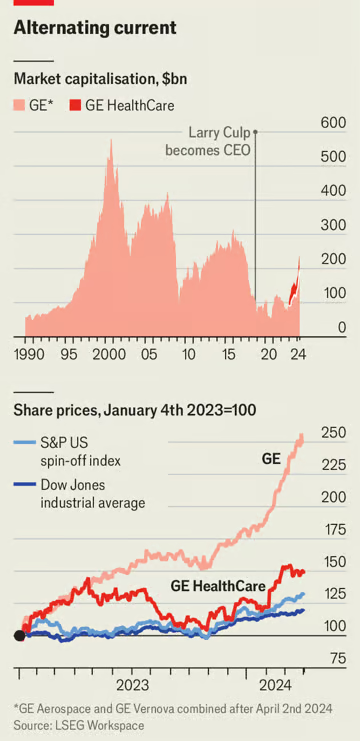

Investors are not mourning the end of ge as they, their fathers, grandfathers and great-grandfathers knew it. On the eve of the split the company’s market value hovered at around $190bn. The next day the two new firms were worth nearly $200bn—and some $240bn if you add ge HealthCare (see chart). In November 2018, shortly after Mr Culp took over as boss, the whole group was worth $65bn, the least since the early 1990s. That June it had been ignominiously kicked out of the Dow Jones industrial average, an index of American blue-chip firms. In the past year both ge and ge HealthCare have handily outperformed the Dow. Their shares have also done better than those of most American spin-offs. Mr Culp says that the group could not continue as an “all-singing, all-dancing ge”. Instead, ge’s corporate progeny will become less general and, amid the energy transition, more electric.

Investors are not mourning the end of ge as they, their fathers, grandfathers and great-grandfathers knew it. On the eve of the split the company’s market value hovered at around $190bn. The next day the two new firms were worth nearly $200bn—and some $240bn if you add ge HealthCare (see chart). In November 2018, shortly after Mr Culp took over as boss, the whole group was worth $65bn, the least since the early 1990s. That June it had been ignominiously kicked out of the Dow Jones industrial average, an index of American blue-chip firms. In the past year both ge and ge HealthCare have handily outperformed the Dow. Their shares have also done better than those of most American spin-offs. Mr Culp says that the group could not continue as an “all-singing, all-dancing ge”. Instead, ge’s corporate progeny will become less general and, amid the energy transition, more electric.

For much of its history ge was synonymous with size. Under Jack Welch, the acquisitive ceo who ran it from 1981 to 2001, it became the world’s most valuable company. Subsequent losses at ge Capital, its bloated finance arm, and troubles in its core industrial businesses laid the giant low. Jeff Immelt, Welch’s successor, sold off ge’s media, home-appliance and, belatedly, finance assets but spent $11bn on the ill-timed takeover of a power-and-grid business of Alstom, a French conglomerate, and $7bn on a stake in Baker Hughes, a purveyor of oil-industry gear. John Flannery, who replaced Mr Immelt in 2017, had the idea of spinning off the health-care division and focusing on ge’s core businesses: aviation and power generation. But he was dumped barely a year into the job, as ge’s share price cratered.

As a result, Mr Culp, the first outsider to run ge, inherited a mess. ge ended 2018 with a $23bn write-down of its power business (largely due to the Alstom deal), a $15bn capital shortfall in a rump reinsurance business, a net annual loss of $22bn and more than $130bn in debt. On paper his rescue plan looked similar to Mr Flannery’s: hive off health, double down on aircraft engines and power. The way he went about it, though, was different.

He halted his predecessor’s proposed spin-off of the health-care division, realising that ge would be too weak in the short run to survive without the successful unit’s income. Instead he sold ge’s biotechnology business to his old employer, Danaher, another industrial group, for $21bn; accelerated the move towards cleaner energy by divesting the stake in Baker Hughes; and flogged ge’s aircraft-financing unit for more than $30bn. He also cut the quarterly dividend from 12 cents a share to a cent. Taken together, these moves reduced ge’s debt by some $100bn.

Critically, Mr Culp understood that reforming ge required not just changes to its structure but also to its operations. Six Sigma, a series of techniques championed by Welch that aimed to keep manufacturing defects below 3.4 per million parts, had become a barrier to innovation and was dropped. Instead Mr Culp introduced ge to “lean management”, which looks for small changes that add up to big improvements over time. This approach, pioneered by Toyota in Japan, involves managers solving problems by visiting the factory floor or their customers, rather than from the comfort of their desks.

Today ge executives pepper their disquisitions with Japanese terms such as kaizen (a process of continuous improvement), gemba (the place where the action happens) and hoshin kanri (aligning employees’ work with the company’s goals). More important, Mr Culp and his underlings routinely spend a week on the factory floor alongside workers. The company credits this system for improvements such as reducing the total distance a steel blade for one of its gas turbines travels during the manufacturing process from three miles (5km) to 165 feet (50 metres), and slashing the time to build a helicopter engine from 75 to 11 hours.

All this puts the two daughter firms in fighting shape to thrive as their sister, ge HealthCare, has done. In 2023 ge Aerospace and ge Vernova generated combined revenues of $65bn, up from $55bn the year before. Engines made by ge Aerospace, the group’s most profitable division, which Mr Culp has chosen to run after the break-up, power three-quarters of all commercial flights. ge Vernova’s gas and wind turbines generate a third of the world’s electrical power.

Like many successful managers, Mr Culp also has luck on his side. Demand for passenger jets—and thus the engines that keep them aloft—is rebounding sharply from a pandemic slump. With a backlog of orders until the end of the decade, ge Aerospace expects adjusted operating profit to surge from $5.6bn in 2023 to $10bn by 2028. The turbulence at Boeing, which ge supplies with engines for the planemaker’s troubled 737 max planes, means that airlines facing delayed deliveries of these narrowbody workhorses will need to stretch their exisiting fleet. That, points out Sheila Kahyaoglu of Jefferies, an investment bank, increases demand for ge Aerospace to keep older engines going. Last year the services business accounted for almost 70% of the division’s revenues.

The winds look favourable for ge Vernova, too. Operating margins in the business rose from low single digits in 2019 to almost 8% in 2023. The International Energy Agency, an official forecaster, reckons that demand for electricity will grow by more than half by 2040 as power-hungry data centres and electric cars guzzle more of it. America is lavishing subsidies and tax breaks on renewable-energy projects. Scott Strazik, a ge veteran who will run ge Vernova, believes that this will help the company attain the scale necessary to spread the high costs of wind-turbine manufacturing, which is still lossmaking.

ge’s run of good fortune may not last. Projections for traffic in the notoriously cyclical airline business may turn out to be too rosy. If Boeing doesn’t pull out of its nosedive, ge Aerospace’s order books could take a hit. The transition to clean energy in America, ge Vernova’s largest market, has been fitful even under Joe Biden, its climate-friendly president. Should the carbon-cuddling Donald Trump return to the White House next year, he has vowed to gut green subsidies. ge’s businesses, in other words, face many and serious difficulties ahead. But at least reorganisation is not one of them.