Military conscription is on the agenda in the rich world

Belly down in a muddy Dutch forest, Sabrina van den Goorbergh fires blanks from a Colt c7 assault rifle. The third-year medical student is taking part in the Dienjaar (service-year), a new programme that lets young Dutch sign up for a year-long trial in the armed forces rather than the regular four-year enlistment term. The programme is a success, drawing three applicants for each spot, and the government plans to scale it up from 625 to 1,000 trainees next year.

Yet it can hardly begin to solve the country’s recruitment problems. The Dutch armed forces number 49,000, less than a fifth of their size during the cold war, and one in ten positions is vacant. Last year regular enlistment yielded just 3,600 of a hoped-for 5,000 new soldiers. This is at a moment when, in the face of the largest war on the continent since 1945, many European countries actually want to expand their armed forces, not just maintain them. By 2030 Germany hopes to raise its troop strength from 182,000 to 203,000, and France from 240,000 to 275,000 (see chart 1). Poland plans to go from 197,000 to 220,000 by the end of this year, and eventually to 300,000.

Yet it can hardly begin to solve the country’s recruitment problems. The Dutch armed forces number 49,000, less than a fifth of their size during the cold war, and one in ten positions is vacant. Last year regular enlistment yielded just 3,600 of a hoped-for 5,000 new soldiers. This is at a moment when, in the face of the largest war on the continent since 1945, many European countries actually want to expand their armed forces, not just maintain them. By 2030 Germany hopes to raise its troop strength from 182,000 to 203,000, and France from 240,000 to 275,000 (see chart 1). Poland plans to go from 197,000 to 220,000 by the end of this year, and eventually to 300,000.

The problem is that today’s career-oriented, individualistic young people are reluctant to join up. And it is not just Europe that is struggling with recruitment. In and around the world’s conflict hotspots the question of how to get more people into uniform is vital. Some countries are reconsidering an old solution: mandatory military service for young people (or young men), often for school-leavers. Terminology varies. Conscription typically means compelling civilians to enlist in the armed forces, whereas military service often refers to a subset of that—ordering young people to do a stint in the forces.

At the start of the 20th century around 80% of countries had some form of conscription; by the mid-2010s it was just under 40%. The practice reached its peak during the world wars, and many countries continued to rely on it throughout the cold war. Thereafter the West’s focus turned to high-tech counterinsurgency campaigns such as those in Afghanistan and Iraq. Mass-conscript armies were mostly replaced by smaller, professional volunteer forces. Since 1995, 13 members of the oecd, a club of mostly rich countries, have scrapped conscription. All but eight of nato’s 32 members have done away with it. But authoritarian countries such as Iran, North Korea and Russia have doubled down on their press-ganged armies.

The most urgent discussion around mandatory military service and conscription is in countries that face a serious threat of war, or are already in one. Take Ukraine. More than two years on from Russia’s invasion, thousands of men there are fleeing across the country’s borders, or hiding, to avoid being served enlistment papers. On April 2nd a lack of troops meant Ukraine’s government was forced to lower the minimum age of conscription from 27 to 25. Russia has thrown hundreds of thousands of forcibly mobilised men into the meat-grinder of its war.

In Israel, military duties are a central pillar of citizenship. After the October 7th attacks, some 300,000 Israelis left civilian life and rushed to join their units. Israel wants to lengthen male conscripts’ service to three years (young women currently serve for 24 months and young men for 32) and to extend the call-up age for reservists to 45. At the same time, ultra-Orthodox Jews’ exemption from service is the subject of a bitter political struggle.

Meanwhile in Asia, Taiwan is trying to prepare for a possible war with China as Sino-American tensions persist. Taiwan extended military service in 2022, from four months to a year. But the island still boasts just 169,000 active soldiers (China has around 2m). South Korea, where military service has a brutish reputation, is trying to make it more appealing. Service has been shortened to 18 months, wages are rising and sadistic drill-sergeants have been pruned. The government also wants to hire more women (men-only conscription has fuelled male resentment and anti-feminist politics).

In many places recruiters for the armed forces are struggling in the face of shifting values: young people have grown averse to fighting even in defensive wars. For decades the World Values Survey (wvs), an academic research project, has been asking people around the world the same question: “Would you be willing to fight for your country?” In the survey’s most recent round, between 2017 and 2022, just 36% of Dutch 16- to 29-year-olds said yes (see chart 2).

In many places recruiters for the armed forces are struggling in the face of shifting values: young people have grown averse to fighting even in defensive wars. For decades the World Values Survey (wvs), an academic research project, has been asking people around the world the same question: “Would you be willing to fight for your country?” In the survey’s most recent round, between 2017 and 2022, just 36% of Dutch 16- to 29-year-olds said yes (see chart 2).

Recruiters try to counter with the rhetoric of patriotism, self-fulfilment and shared values; the emphatic slogan of Germany’s armed forces, the Bundeswehr, is Wir. Dienen. Deutschland. (We. Serve. Germany.) They also run campaigns with influencers on TikTok and Instagram. But it does not seem to be enough to hit their targets.

This is partly to be expected. As countries get richer, their citizens tend to become less eager to sacrifice themselves for the nation. Herfried Münkler, a German political scientist, called Western democracies “post-heroic” societies, in which “the highest value is the preservation of human life” and personal well-being. History certainly plays a role. Willingness to fight is low in the countries that lost the second world war (Germany, Italy and Japan). In Spain and Portugal, decades of military dictatorship left many citizens suspicious of the armed forces.

But things can change when conflicts draw near. According to a forthcoming paper by Wolfgang Wagner and Alexander Sorg of the vu University in Amsterdam and Michal Onderco of the Erasmus University in Rotterdam, proximity to war makes citizens more willing to fight. In Europe, this helps explain why countries close to Russia are less doveish.

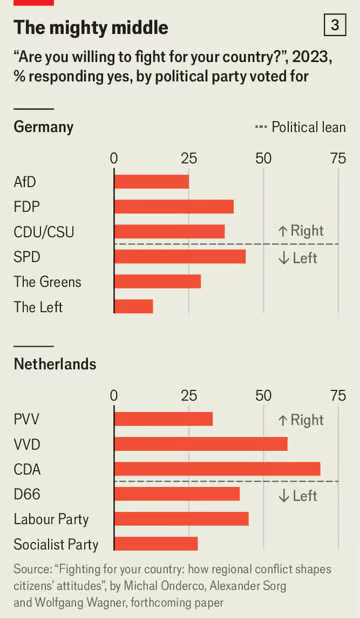

Political alignment is a poor predictor of willingness to bear arms. “The radical right is not so eager to fight,” says Mr Wagner, at least in Germany and the Netherlands. Last year he and his colleagues commissioned a study in those countries which found that few people who planned to vote for either far-left or far-right parties were willing to fight for their country. Those who backed centrist parties, such as Germany’s Social Democrats and Christian Democrats, were more prepared to do so.

Political alignment is a poor predictor of willingness to bear arms. “The radical right is not so eager to fight,” says Mr Wagner, at least in Germany and the Netherlands. Last year he and his colleagues commissioned a study in those countries which found that few people who planned to vote for either far-left or far-right parties were willing to fight for their country. Those who backed centrist parties, such as Germany’s Social Democrats and Christian Democrats, were more prepared to do so.

Besides changing values, military recruiters face an economic hurdle: young people currently have lots of employers bidding for their services. In most wealthy countries, Generation Z has its pick of jobs. Unemployment among 15- to 24-year-olds in the European Union was 14.5% last year, down from 22.4% in 2015. In Germany it was just 5.8%. In such tight labour markets, armies have a hard time competing with the private sector. Besides, sitting at a desk is rather nicer than crawling through mud.

In some wealthy countries, however, young people’s willingness to fight remains high. In France the share is 58% in the wvs. The figure is higher still in Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea. In Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden, four of the wealthiest and most peaceful countries in the world, two-thirds or more of citizens say they are willing. (All are close to Russia.) Their expanding armed forces also have no trouble finding soldiers: all four have compulsory military service for young people.

Sweden actually eliminated the practice in 2011, but brought it back in 2018 after failing to meet recruiting targets. It is an intriguing case study for others. Having just joined nato, it is scaling up from 69,700 to 96,300 soldiers, which requires about 10,000 recruits a year. All of the country’s 19-year-olds (men and women) must fill out service questionnaires; a bit under a third qualify, and a tenth are ultimately inducted.

Rather than souring young people on the armed forces, in Sweden mandatory service seems to make them more enthusiastic. In exit surveys at the end of their stints, “about 80% of the conscripts would recommend other young people to do military service”, says Pal Jonson, the defence minister. Some 30% re-enlist as soldiers or reserves. Because more young people qualify than are needed, only the best candidates make it in, and military service looks good on one’s cv.

This kind of conscription helps keep Nordic armies a melting-pot for different classes, and discourages political polarisation. (Volunteers in armed forces tend to skew towards the right; in Germany neo-Nazi cells have been uncovered in the Bundeswehr.) In the Middle East too, many states see military service for young people as a social adhesive. The United Arab Emirates introduced it in 2014 partly to forge a sense of shared identity among its youth. Morocco, Jordan and Kuwait have followed suit.

You got no time to lose

Shortfalls across many democratic states suggest that better recruitment strategies can do only so much to boost troop numbers. Few medical students have Ms Van den Goorbergh’s drive to take up infantry training on the side. In liberal societies, large segments of the population have come to see serving in the army as someone else’s job. Reintroducing obligatory military service for youngsters might be politically and practically unworkable for the same reason recruitment is falling short: citizens feel alienated from the armed forces.

Yet the Nordic model seems to help bridge that gap, ensuring that military service remains a natural part of social life and nudging more school-leavers to consider a related career. Other youngsters may still only join up in a crisis. “It is fear that moves you to action,” says Andrei, a former television producer now fighting in eastern Ukraine. He signed up the day after Russia invaded. Most Ukrainians did not believe they would ever have to fight for their country, either.