Educated voters usually disdain populists. Three factors explain why India’s leader is different

Narendra modi, India’s prime minister, is often lumped together with right-wing populists such as Donald Trump or Viktor Orban. On the surface, the comparison is plausible. In 2019 Mr Modi told the Indian Express, a newspaper, that his electoral success was not due to “the Khan Market gang or Lutyens Delhi”, monikers for India’s old establishment. Rather, said Mr Modi, he pulled himself up through “45 years of toil”. But the prime minister, who is expected to win a third term after India goes to the polls later this month, is no ordinary strongman.

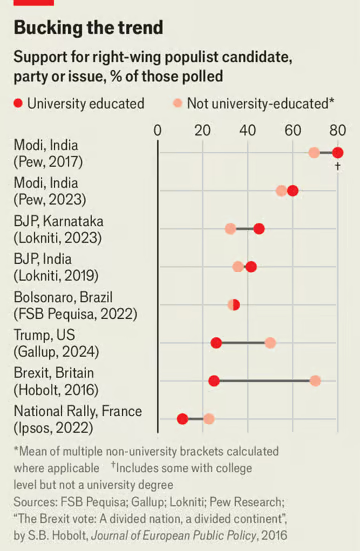

In most places support for anti-establishment populists, such as Mr Trump, and policies such as Brexit tends to be inversely correlated with university education. Not in India. Call it the Modi paradox. It helps explain why he is the most popular leader of any major democracy today.

In most places support for anti-establishment populists, such as Mr Trump, and policies such as Brexit tends to be inversely correlated with university education. Not in India. Call it the Modi paradox. It helps explain why he is the most popular leader of any major democracy today.

A study in 2020 of Britain, Turkey, eight countries in the European Union and five in Latin America by Cristóbal Rovira and Steven van Hauwaert, two political scientists, confirmed the inverse relationship between higher education and support for populist leaders. It is not universal: Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s president from 2019 to 2022, was backed by some of the best-educated elites. But in America it is strong. In December 2023 Gallup, a pollster, found that just 26% of respondents with a university education approved of Mr Trump, compared with 50% of those without.

Mr Modi bucks this trend altogether (see chart). In 2017, 66% of Indians who had no more than a primary-school education told Pew Research that they had a “very favourable” view of Mr Modi. The number rose to 80% among Indians with at least some higher education. After the previous general election, in 2019, Lokniti-csds, a pollster, found that around 42% of Indians with a degree supported Mr Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (bjp), while around 35% of those with only a primary-school education did. Polls conducted after state elections in 2023, such as in Karnataka, confirm the trend. Similarly Pew’s latest survey, from last year, shows that 60% of university-educated Indians have a very favourable opinion of Mr Modi, compared with 55% of those who do not have a degree.

A psephological puzzle

Mr Modi’s success among the well-educated does not come at the expense of support among other groups. Indeed, like other populist leaders, his biggest inroads have been made among lower-class voters, says Neelanjan Sircar, a political scientist at the Centre for Policy Research, a think-tank in Delhi. In 2020 Sanjay Kumar of the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies found that between 2014 and 2019 support for the bjp increased among rural, lower-caste, young and poor voters. It grew especially quickly among “other backward classes”, which make up nearly half of the population. Among them, the bjp’s support rose from 34% to 44%, compared with an increase of 31% to 38% among all voters.

This pattern of support for the bjp is comparable to other countries in which less-educated or rural people have shifted right. But unlike many of his counterparts abroad, Mr Modi has also been able to increase his support among the educated. Three factors—class politics, economics, and elite admiration for strongman rule—help explain why.

In India, class is intertwined with the caste system. The bjp, like many conservative parties, is known to be business-friendly. A core constituency includes much of the “Bania” trader community, a traditionally business-oriented group concentrated in states such as Gujarat and Rajasthan. Tycoons such as Mukesh Ambani and Gautam Adani, India’s richest men, fall into this group. Upper-caste Hindus, including Kshatriyas and Brahmins, are also part of the core support base. Some regional parties, such as the dmk in Tamil Nadu, have positioned themselves against such upper-caste groups. Congress, the main national opposition party, has championed preferential access to education and government jobs for lower castes.

Bigger, better…strongman?

Mr Modi, himself from a relatively low caste, has marketed the bjp as a caste-agnostic “pan-Hindu” party. This means he retains support from high-caste groups while extending the party’s reach to others. Mr Sircar notes that the well-educated professional class across India broadly does not identify with the bureaucrats and media types in Delhi. So Mr Modi’s antipathy to the capital’s elite has not cost him support among others elsewhere.

The second factor is economic. Annual gdp growth was 8.4% in the last quarter of 2023 (though because of quirks in how India measures its gdp, the underlying figure is closer to 6.5%). That growth, albeit unequally distributed, is driving a rapid increase in the size and wealth of the Indian upper-middle class. Goldman Sachs, a bank, has called this phenomenon the rise of “affluent India”. It calculates that the number of Indians with an annual income of $10,000 or more grew from 20m in 2011 to 60m in 2023, and will hit 100m by 2027.

It is not surprising that Mr Modi has retained the support of those who have become richer. The Congress party enjoyed strong support among the upper-middle class during the fast-growing late 2000s. It took a slowdown and a series of corruption scandals in the 2010s to change things.

But Mr Modi’s tenure has increased India’s economic and geopolitical standing in the world, too. One fund manager in Mumbai says that her friends worried about perceptions of India when Mr Modi was elected prime minister. He was chief minister of Gujarat during a bloody riot against Muslims there in 2002, an incident that saw him denied a visa to America for nine years. She thought Mr Modi might become a global pariah. In fact, the opposite happened. Because of India’s economic heft, and its importance as a counterweight to China, Mr Modi has been embraced by leaders worldwide.

Many university-educated Indians say they dislike Mr Modi’s weaponisation of law enforcement against opposition parties and his government’s treatment of Muslims as second-class citizens. The arrest on March 21st of Arvind Kejriwal, the chief minister of Delhi, amplified these concerns. Still, as a banker in Mumbai notes, there is a widespread sense that the good parts of Mr Modi outweigh the bad. Indeed, some think a dose of strongman rule is exactly what India needs.

This is the third reason for the prime minister’s popularity among elites. They point to China and the East Asian tigers, which they believe show that muscular governance can tear down barriers to economic growth. One industrialist in south India says that the country is “probably too democratic”, given its level of income. Mr Modi, he adds, can “get shit done”.

India’s elites see Mr Modi’s foreign policy as nationalist yet pragmatic. They like the way he thumbs his nose at liberal Western institutions and the media, in a similar fashion to other anti-globalist strongmen, while promoting Indian interests. Mr Modi has negotiated four new trade deals since 2021, most recently with a grouping of four non-eu European countries on March 10th. In February, at the Raisina Dialogue in Delhi—India’s version of the Munich Security Conference—his ministers lamented the un’s antiquated structure, while also positioning India as the leader of the global south.

Admiration for leaders perceived as decisive is not new among India’s elite. In the 1970s J.R.D. Tata, one of the country’s most prominent industrialists, is said to have appreciated Indira Gandhi’s imposition of “the Emergency”, a two-year-long suspension of normal democratic processes in response to a perceived threat to her power. A survey by Pew published in February found that 67% of Indians thought that “a system in which a strong leader can make decisions without interference from parliament or courts would be a good way of governing their country”. That figure, up from 55% in 2017, was the highest among the 24 countries surveyed. Many internationally minded Indians say Mr Trump is too autocratic for America, but that Mr Modi is the right man for their country.

Making India great again

So what could shake Mr Modi’s elite fan base? Continued weaponisation of the state, as in the case of Mr Kejriwal, could come back to bite him; most elites still say they believe in democracy. And many of the people who say they like the prime minister also fear him, including those in business who know their survival depends on remaining in his good graces. Some have tempered their support. Pew’s survey in 2023 found that 17% of college-educated respondents had an unfavourable view of Mr Modi, up from 5% in 2017.

Others are voting with their feet: according to Henley and Partners, a consultancy, India had a net outflow of 14,000 millionaires in 2022 and 2023, more than any country among those measured bar China, including Russia. By contrast Australia, Singapore and the uae, and eight other countries, attracted over 1,000 millionaires each in net inflows—reflecting, perhaps, their more predictable rule of law.

But for those who stay, even intensified autocracy may not be enough to lose Mr Modi many votes. In 2019 India’s economy, reeling from a mini-financial crisis, slowed to a growth rate of 4%. While this weakness was not entirely Mr Modi’s fault, his impulsive decision to swiftly demonetise large banknotes in 2016 had not helped. Elites complained, but apparently felt that Mr Modi was better for their wallets than the opposition, and voted for him.

This is why many say that support for Mr Modi will continue until a credible alternative appears. Most elites have lost faith in Congress and its leader, Rahul Gandhi, who is seen as dynastic and out of touch. One senior Congress official even admits that Mr Modi “has taken our best ideas”, such as distributing welfare payments digitally, and “executed them better” than his party could have done. A stronger opposition is probably the only thing that will cause India’s elites to abandon Mr Modi. For now, however, that is nowhere in sight.